Indignity Vol. 2, No. 47: The word made flesh.

ANDY ROONEY 2.0 DEP'T.

Where Is the NBA Finals Logo?

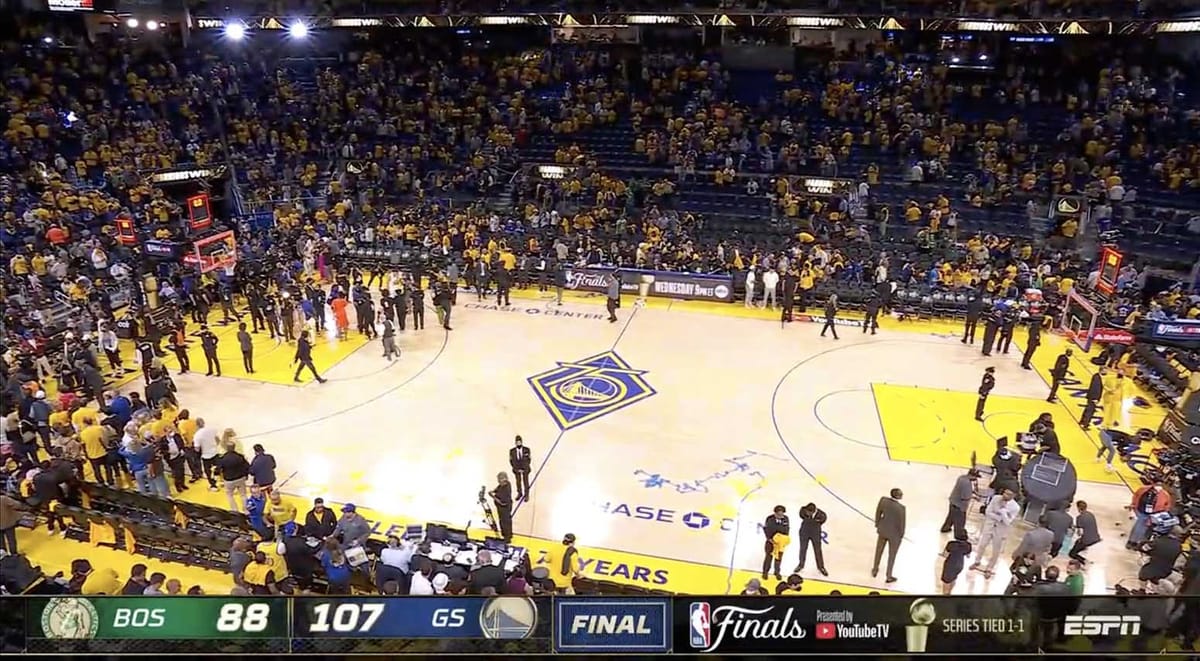

THIS IS HOW to learn something about reality in 2022: someone posted, on Twitter, an off-kilter photograph of a video screen showing the broadcast of the NBA Finals. In the photo, Payton Pritchard of the Boston Celtics was dribbling a basketball—a feat that looked more difficult than normal because his right arm, the dribbling arm, ceased to exist about halfway up the humerus. There was the ball, and then the hand, forearm, and elbow floating in space, and then the rest faded into a gap all the way up to where Pritchard's jersey began.

In the empty space where Pritchard's deltoid should have been was the lowercase letter I of the word "Finals," in script, from the logo that was supposed to be—that is, the logo that was supposed to appear to be—on the floor behind him. "NBA’s logo technology was not prepared for a player the same color as the court," the author of the tweet, Ryan Perry, wrote.

NBA’s logo technology was not prepared for a player the same color as the court

— Ryan Perry (@rynprry) 2:03 AM ∙ Jun 6, 2022

This was one way of looking at it, although it might be more that, confronted with the ostentatiously tasteful blond-wood decor of the Golden State Warriors' new arena, the technology was not prepared for a floor the same color as a player. But the thing that stuck with me about the glitch was: who knew technology was involved at all?

Until I saw the picture of the text clipping through a human arm, I had been assuming the Finals logos were physical marks on the floor of the arena, the way they always used to be. Or rather, I hadn't been consciously thinking about the logos at all. The Finals were on, they had the word "Finals" on the floor, and that was normal.

Yet it wasn't. The NBA made a big deal about the Finals logo this year, announcing that, after a few years of a blocky text emblem, the league had created a "reimagined" version for its 75th anniversary, reviving the old "iconic script font" that had been used off and on since the 1980s (while still including the "Presented by YouTubeTV" slogan from the most recent version). Publications duly relayed the message; apparently there were fans of the script treatment, and they were happy to hear it was being revived. The post about the new logo on For the Win used an archival photo of a worker on an arena floor, peeling up the covering of a freshly installed Finals script decal.

The NBA release did not mention that this return to the old Finals lettering was not, in fact, the return of any physical lettering to the floors where the Finals would be played, but a computer-generated insert; that is, it was a computer-generated on-court advertisement for YouTubeTV. One of two ads at each end of the floor, really, because the computer is also inserting a standalone YouTubeTV logo, rotating with other ads, between the side of the lane and the three-point line.

But now, somewhere inside the rendering rules, the unreality of the ad had momentarily outranked the physical presence of a player. At least, it had if the tweet could be trusted, given how strained our everyday connection to the actual is. It's not unimaginable, at present, that someone could have mocked up a TV glitch to make a joke about Pritchard's complexion. But it would have been a stretch, and a news photograph of the arena confirmed the basic premise: there is no Finals logo on the Warriors' floor.

Further checking, moreover, established that there was no Finals logo on the floor for last year's Finals, either. It's there in the TV highlights (on YouTube), but not in the game photographs. There hasn't been a real floor logo since the immense one that occupied most of the midsection of the court when the Finals were played inside the league's Covid bubble in Disney World in 2020.

I watched last year's Finals pretty attentively, and I never caught on. In retrospect, when I watch highlight clips now, the Finals logo and the separate YouTubeTV logo look noticeably blearier than the high-definition players. But back then, I was watching the players. The markings on the floor never jumped in front of anyone's limbs, so I never realized they weren't truly there.

Sportscasts have been adding more and more augmentation or fakery since the NFL brought in the glowing virtual first-down line in the '90s. Olympic ski jumpers soar toward a glowing target line; national flags float in the lanes of the swimming pools. Baseball games post the circle where the baseball arrived, relative to the hovering box of the strike zone, to second-guess the umpire faster than the umpire can first-guess. And since anything that communicates information can also be used for advertising, we get ever-changing virtual billboards behind home plate—or, at the just-completed French Open, a naturally scuffed-looking advertisement for Jersey Mike's Subs digitally painted by NBC on the red clay behind the near baseline at Roland Garros.

The NBA Finals logo isn't an overlay or a marketing adjacency, though. It's a texture pack of the ersatz, installed right onto the middle of what's being presented as physical reality—the uncanny meeting the unnecessary. Like George Lucas jamming more and more CGI starfighters into the revised frames of his original Star Wars movies, sports producers will keep on doing whatever the technology enables them to do, or to almost do. Now and then during last year's baseball All-Star home run derby, the view of the events would swing on a loop through space. I originally started to write "at" instead of "during," and "camera" instead of "view of the events," but those were the wrong terms: the shots were not from the lens of a moving camera, and the image was not taken at Coors Field.

Instead, a computer somewhere was taking data from the real camera feeds and manipulating it to produce an artificial scene. Shohei Ohtani, awaiting his turn, suddenly transmuted into something faintly plasticky and unalive—a rendering of himself from a cutscene in a not-quite-realistic-enough video game—as the not-a-camera moved around him. The technique was supposed to take the audience deeper into the world of the home run derby. Instead, it pushed the viewer out of the world entirely, toward someplace no human could quite exist.