The Stairs, Chapter One

Indignity Vol. 5, No. 198

HAPPY FRIDAY! THIS is your editor emeritus, Tom. I am now fully ensconced in my new full-time journalistic job, under the terms of which, as previously discussed, I am barred from publishing nonfiction in outlets other than the one that employs me. Therefore, as also previously discussed, Indignity will be bringing you a serialized work of fiction by me. It is a novel for young readers, titled The Stairs. There should be about 45 more chapters following this one, depending on editing decisions. I hope you, or any young readers in your life, enjoy it.

THE STAIRS

© Tom Scocca, 2025

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual people, places, and events is entirely coincidental, with the exception of the events in Chapters One and Two, which happened more or less as written, on the line between Cambridge and Somerville, Massachusetts, on Memorial Day weekend in 1999.

1.

The natural question you're going to ask is, how could I not have noticed the door? It didn't make much sense to me either, and I'm the one who didn't notice it: a full-sized extra door, in my own bedroom. I had looked right past it for six months.

To be fair, there had been a dresser in front of it before. And it hadn't been my bedroom, exactly, to that point. None of the apartment had been ours. We'd moved in temporarily, with it already furnished.

Basically my mom had come to Marble City to be a visiting lecturer, as they called it, at Marble College. It was almost a new job, but not quite. She was supposed to try the job on for six months, from January to June, and see if she liked doing it better than her old job, while Marble College would see if they liked her doing it.

Meanwhile the college set her up with this apartment that someone else had been living in, while that person had gone off to be a visiting lecturer somewhere else: their dressers, their bookshelves, their beds, their pots and pans and plates in the kitchen. Their forks and spoons. The forks had weirdly wide tines, and the spoons were kind of flat.

So we had just sort of moved into someone's else's life in Marble City: unpacked our bags and put our clothes in the drawers and the closets and put our toothbrushes in the bathrooms—there were two bathrooms, though the one I shared with my little brother didn't have a bathtub in it, just a shower stall. My little brother is Theo; I'm Rollo. Rollo Zulli. I didn't mind the shower. I was used to taking showers, because I'm 11, but Theo is 7, and till we left our old apartment in Turfburg, he had only been used to taking baths.

Our dad had stayed down in Turfburg, working at his old job and keeping up our old apartment. Two or three weekends a month he would drive up to see us, and sometimes we would go down there. But he and Mom had decided it would be good for Theo and me to go stay with her and see what it was like to live in a different place for a while.

I wasn't at all sure about that. I was used to Turfburg. I knew my way around it, literally. We used to ride the circulator bus so I could see it all.

Mom and Dad got me a Marble City atlas, a big spiral-bound one, and a bus guide—and a subway map, because Marble City has a real subway. I couldn't deny that the subway was an attraction. Before we left Turfburg, I read the atlas front to back, and back to front again, trying to see what we were in for.

Turfburg is just one big town, or small city, with the streets numbered out in quadrants from the heart of downtown: Fifth Street Northeast, Third Avenue Southwest, etc. It was easy to know where you were. Marble City was bigger and more complicated, even on paper. Four different towns or cities—they called them boroughs—all mashed together into one. The streets lined up one way in one place, and a different way in another one, or they didn't line up at all.

Even the apartment was off kilter. It was a funny shape: the building was in between two streets where they came together in a V—or in a Y, if you included the part where the bigger street kept going—and the living room tapered to a point, with a bay window in the end.

It wasn't a very big building, five floors, with only one apartment per floor. The ground floor had been an empty pizza parlor when we moved in, and now it was a new record store selling old records. We were on the second floor.

You would think that pointy part of the living room would have been a great place to sit and look out of, like the prow of a ship, but the other people had for whatever reason decided that was where to put their bicycle rack, so the closest we could really get to that end was on the couch, which was against the wall, angling away. To try to get any use out of the window, we had to crane our necks from there and peer through the bikes.

That was how it had been for those six months, and then our mom told us that the college had asked her to stay in Marble City and be a regular lecturer, and that the person whose things we were living with had decided to stay in the city where they were visiting too. And so on June 30, a crew of movers came and carried off all the stuff that had been in the apartment, the couch and the bikes and everything else.

Our own furniture, from the apartment in Turfburg, was on a truck that was coming July 3, with Dad. He had arranged with his job to move up to Marble City for good. Going back and forth, I hadn't really felt like either place was home, but now all of us and all our stuff were going to be together again.

Until then, the apartment was suddenly empty. Theo and I had crammed our clothes and toys and books back into our suitcases, and Mom had folded up some blankets and comforters into bed-like arrangements on the floor, to get us through the night. We'd been busy all day on the 30th, shoving the stuff we did have this way and that, to clear the way for the movers and to make sure none of our things went out on the trucks.

When they were gone and the trucks drove away, the whole place looked different, as if we were seeing it for the first time. Theo and I scooted along the bare floor in our socks, all the way to the end of the living room, and stood there looking out the bay window at the trees and at the stoplight where the two streets came together. Then we went out and got burgers, because now we had no kitchen table or dining table and no chairs, and the other people's plates and their weird forks and spoons were gone off to rejoin them, too.

The sun stays up really late in the summer in Marble City—the road atlas says it's 340 miles north-northeast of Turfburg—so it was still light out when we got back from the burgers. We were pretty wiped out, though. We called Dad and talked for a little while. His voice sounded echoey in the empty apartment down there, and he told us ours did too. Then Mom went to her room to type on the computer on the floor, and Theo and I flopped down on our blankets, to look at our tablet.

It was only then that I saw the door. It was a real, regular door, with a doorknob, right there on the same wall with the closet door and the bathroom door, toward the left-hand corner as you faced it. I must have looked past the foot of my bed at it every night and every morning, and somehow, till now, I'd missed it. The frame and the hinges and the door were the same off-white as the walls, and that dresser had been there, and my brain hadn't registered it.

"What's that door?" I asked Theo.

"I'd been wondering about that since we moved in," Theo said. He was very matter-of-fact about it.

"You had?" I said.

"You hadn't?" he said.

In my defense—look, there are some things Theo notices, OK, and there are some things I notice. For instance: the temperature. Anywhere between 40 degrees and 80 degrees, Theo doesn't distinguish. I dress appropriately. Or street signs. On the east side of the building, the permit-parking signs are green on white; on the west side, they're black on white.

When I noticed that particular thing, about the signs, I checked in the book of Marble City street maps and it turned out that the boundary line between the borough of West Marble and the borough of Old Marble runs right through our apartment. They have separate parking-enforcement departments and sign shops. Did Theo spot that? He did not. Different people pay attention to different things.

I'll admit that an entire door was a pretty big thing for me to overlook, though. There was a rectangle of dust on the floor in front of it, off center and overlapping, where the dresser had been. "Let's see what's there," Theo said. He got up and walked over, getting dust on his socks.

"I'll do it," I said. "Hang on." Sometimes I have to make sure to take on leadership duties myself, between brothers. Theo is not what I'd call insubordinate, mostly, but sometimes he forgets he's only seven. He stopped there in the dust and waited for me.

The doorknob had been painted white too. I put my hand on it. It felt like metal. Probably it was locked shut. "It's probably locked shut," I told him.

I tried giving the doorknob a turn, to show him, and it turned. The latch clicked. "It's unlocked," Theo said. I gave him a look. He ignored the look. "Open it," he said.

"I am," I said.

I pulled the door open.

The Stairs will continue next week!

EASY LISTENING DEP'T.

Here is the Indignity Morning Podcast archive!

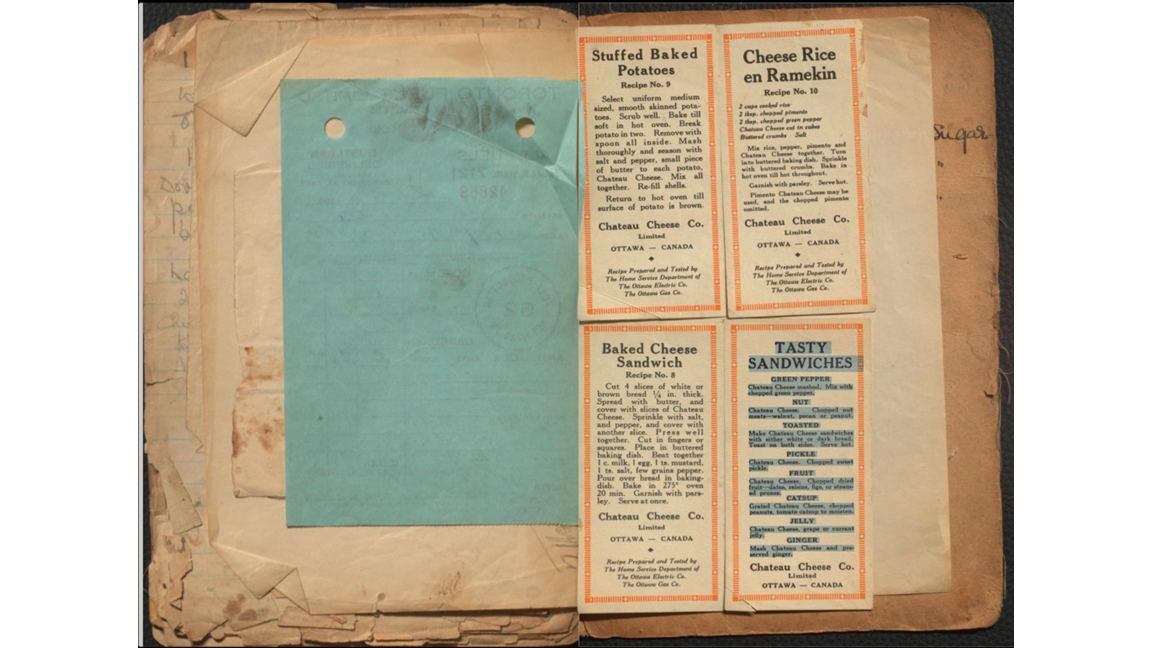

SANDWICH RECIPES DEP'T.

WE PRESENT INSTRUCTIONS for the assembly of sandwiches selected from Canadian Recipes*, by Cynthia Brown, a pseudonym of Rose Marie Armstrong Christie. Jane, as she was known to her family, was the paternal aunt of The Montreal Gazette journalist and author Julian Armstrong. Seven pencil manuscript recipes laid in, one typescript recipe laid in, three small pamphlets laid in, four printed recipes from Chateau Cheese Co. Limited, Ottawa, Canada laid in, one bill for coal delivery laid in. This manuscript was published in 1920 and available at archive.org for the delectation of all.

*Title devised by cataloguer.

Baked Cheese Sandwich

Cut 4 slices of white or brown bread 1/4 in. thick. Spread with butter, and cover with slices of Chateau Cheese. Sprinkle with salt, and pepper, and cover with another slice. Press well together. Cut in fingers or squares. Place in buttered baking dish. Beat together 1 c. milk, 1 egg, 1 ts. mustard, 1 ts. salt, few grains pepper. Pour over bread in baking dish. Bake in 275° oven 20 min. Garnish with parsley. Serve at once.

—Chateau Cheese Co. Limited, Ottawa, Canada, Recipe Prepared and Tested by The Home Service Department of The Ottawa Electric Co./The Ottawa Gas Co.

TASTY SANDWICHES

GREEN PEPPER

Chateau Cheese mashed. Mix with chopped green pepper.

NUT

Chateau Cheese. Chopped nut meats—walnut, pecan or peanut.

TOASTED

Make Chateau Cheese sandwiches with either white or dark bread. Toast on both sides. Serve hot.

PICKLE

Chateau Cheese. Chopped sweet pickle.

FRUIT

Chateau Cheese. Chopped dried fruit—dates, raisins, figs, or steamed prunes.

CATSUP

Grated Chateau Cheese, chopped peanuts, tomato catsup to moisten.

JELLY

Chateau Cheese, grape or currant jelly.

GINGER

Mash Chateau Cheese and preserved ginger.

—Chateau Cheese Co. Limited, Ottawa, Canada

If you decide to prepare and attempt to enjoy a sandwich inspired by this offering, be sure to send a picture to indignity@indignity.net .

SELF-SERVING SELF-PROMOTION DEP'T.

Indignity is presented on Ghost. Indignity recommends Ghost for your Modern Publishing needs. Indignity gets a slice if you do this successfully!