Wireless communication

Indignity Vol. 5, No. 160

TECHNOLOGICAL PROGRESS DEP'T.

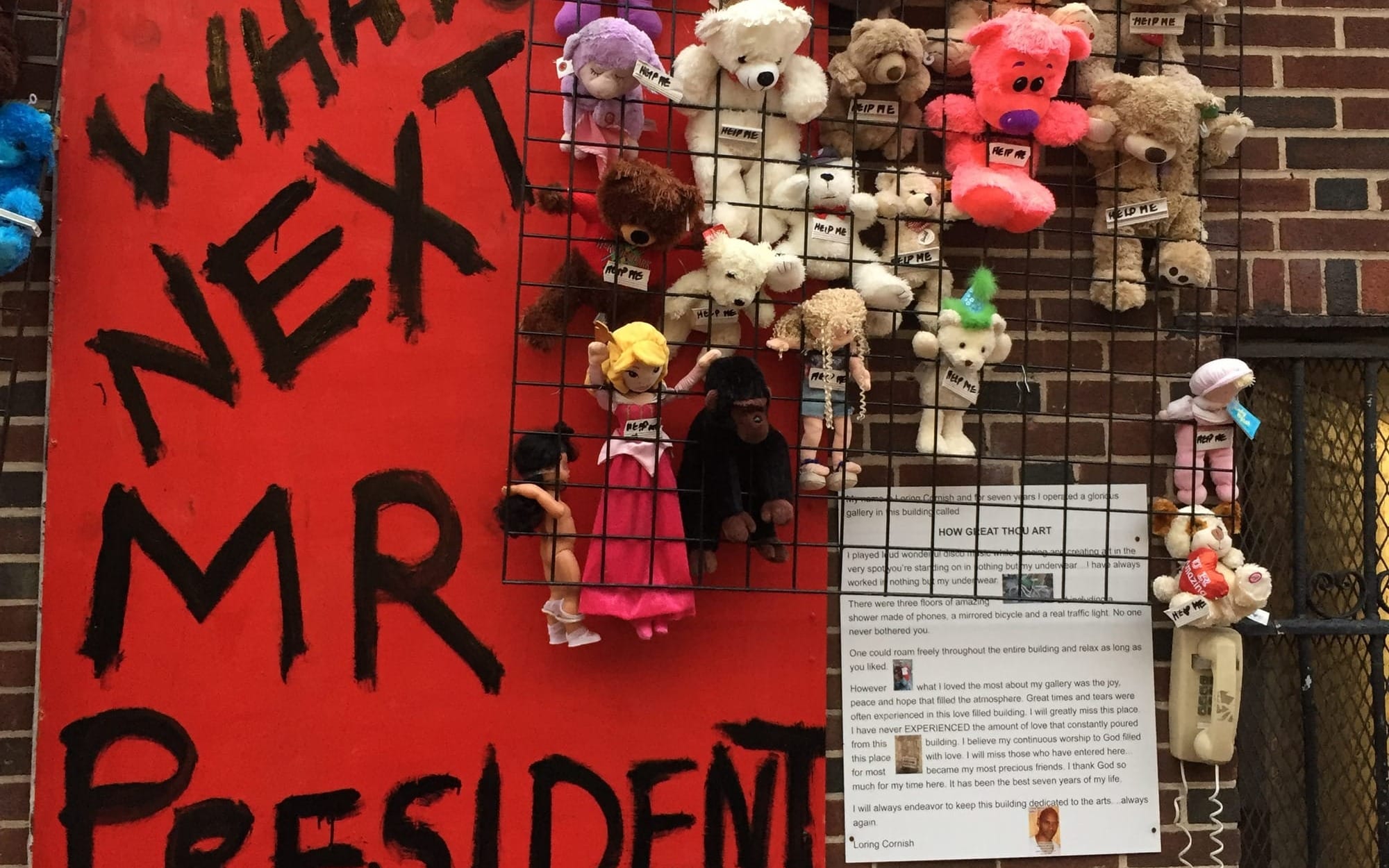

Before the Telegraph, There Was the Other Telegraph

I'VE BEEN READING The Count of Monte Cristo, the Penguin Classics edition, translated by Robin Buss. I'd never properly understood just how much of the novel takes place after Edmond Dantés escapes from prison and lays hands on his incomparable fortune—that entire opening part is wrapped up in less than 250 pages, leaving more than 1,000 pages of story for him to use that wealth and his painfully acquired talents to wreak revenge on the people who wronged him. Nor had I counted on Alexandre Dumas, writing in the mid-1840s, presenting an unambiguously lesbian character ("Not a single glance or sigh from [her suitor] escaped her, but they appeared to be deflected by the breastplate of Minerva, which philosophers sometimes say in fact covered the breast of Sappho").

But so far the thing I least expected in the story happened toward the beginning, not long after Dantés was locked up after being caught as the unwitting courier of a seditious letter from Napoleon, exiled to Elba, to his sympathizers in Paris. The local prosecutor in Marseilles rushes to Paris to warn King Louis XVIII of the intercepted message, in which Napoleon announced his plans to invade and re-conquer Paris. The king is informed of the prosecutor's arrival, and told that "he has just covered two hundred leagues by road, in barely three days."

To this, Louis XVIII replies:

"He has expended a lot of energy and a lot of trouble, my dear Duke, when we have the telegraph that only takes three or four hours, and does so without making one in the slightest bit out of breath."

This was confusing on two counts. First of all, Napoleon escaped from Elba and marched on Paris in 1815. Samuel Morse didn't send "What hath God wrought?" from Washington, D.C. to Baltimore until May of 1844—29 years after Napoleon's return, and only three months before Dumas published the first newspaper installment of The Count of Monte Cristo.

Second of all, Samuel Morse's telegraph would have conveyed a message from Marseilles to Paris in much less time than three or four hours. What was going on?

Soon after, in the story, the telegraph brings word that Napoleon has in fact invaded and is sweeping inland, to which Louis XVIII responds, "To fall...to fall and learn of one's fall through the telegraph! Oh, I should rather mount the scaffold like my brother Louis XVI, than to descend the steps of the Tuileries in this way, driven out by ridicule.'"

Clearly, the monarch is talking about some technological innovation, powerful but also unseemly in its novelty. But it cannot not involve electrons speeding along a wire. Instead, France had its own entire pre-electric system for transmitting written messages (as in "-graph") over distances (as in "tele-"): the optical telegraph, invented by Claude Chappe and deployed starting in the 1790s.

By the 1840s, the economist Alexander J. Field wrote in "French Optical Telegraphy, 1793-1855: Hardware, Software, Administration," a 1994 article in the journal Technology and Culture, the Chappe telegraph network "covered almost 5,000 kilometers, comprising over 530 relay stations within the current geographic borders of France":

During wartime, its reach was international: at the height of the Napoleonic period (1810), lines ran west from Paris to Brest, north to Amsterdam by way of Lille and Brussels, east to Mainz in Germany by way of Metz and Strasbourg, and southeast to Lyons and then across northern Italy to Venice by way of Milan.

The Chappe system was a collection of elevated signaling stations, spaced five or six miles apart along routes mostly radiating outward from Paris, with one station in sight of the next. Each station had an adjustable device on top, painted black, to be set in various configurations against the sky. An operator would use a telescope to read the position of the neighboring station, then replicate it for the next station down the line.

The mechanism, with pulleys turning two rotating arms at each end of an also-rotating main arm, "defies simple description," Field wrote. Dumas, for his part, has the Count of Monte Cristo hold forth on the telegraph's appearance, not quite 700 pages into the novel:

"Often, at the end of a road, on a hilltop, in the sunshine, I have seen those folding black arms extended like the legs of some giant beetle, and I promise you, never have I contemplated them without emotion, thinking that those bizarre signals so accurately travelling through the air, carrying the unknown wishes of a man sitting behind one table to another man sitting at the far end of the line behind another table, three hundred leagues away, were written against the greyness of the clouds or the blue of the sky by the sole will of that all-powerful master."

Dumas, anticipating the plot of Trading Places (1983), then has the Count bribe a telegraph operator to send a false piece of news that will lead one of his enemies into a disastrous bout of attempted insider trading. The French telegraph was controlled by the government, and the information it carried was encoded; the relay operators simply copied the signals without knowing what they were signaling.

Strings of beacons and other basic signaling devices had been used throughout history—Rome's network of signal towers, Field wrote, crossed into Africa and circled the Mediterranean—but those older systems "were limited to sending simple messages whose content had been anticipated by both sender and receiver." The French telegraph worked as a telegraph because of the system Chappe devised for transmitting messages through it. Rather than sending information one letter or word at a time, the code delivered text grouped into pre-selected common phrases, Field explained, which "were listed in a vocabulaire consisting of 92 pages with 92 entries on each page, or 8,464 precoded groupings communicable with a sequence of two signals." In the daytime, when the weather was clear, that density of information helped make up for the slowness of the signaling process:

Étienne L'Hôpital estimates a transmission rate of 24 bits per minute on the Paris-Lille line and 12.4 bits per minute from Paris to Bordeaux. This compares with approximately 30 bits per minute when a character-based dial telegraph is used [or] 60 bits per minute when Morse apparatus is used.

That was good enough for the telegraph to hang on past the publication of Dumas' novel, even after the Morse system got going. "Slightly modified equipment," Field wrote, "continued to be operated in Algeria even after the system's demise in metropolitan France—the absence of potentially disruptable wires in a politically and militarily unstable environment was deemed an advantage."

WEATHER REVIEWS

New York City, September 7, 2025

★★★ The dull ringing of all the downspouts came together until it sounded as if the bedroom were inside a single giant downspout. It was long-pants weather, entirely. Gradually and reluctantly the rain eased up and went away, and even more gradually the cloud cover followed. Even while the clouds were thinning, there was still water caught in the dogwood leaves and an intermittent dripping kept sounding. Late sun shone down the wall outside and illuminated the construction mesh along the top of the rec center. The air down in the subway was still hot and stale. In the cool of early night, people crowded the sidewalks and open doorways of Times Square, abuzz with their familiar alien tourist energy. Uptown the full moon stood alternately framed and veiled by translucent clouds in a leopard-spotted sky.

EASY LISTENING DEP'T.

HERE IS TODAY'S Indignity Morning Podcast!

Here is the Indignity Morning Podcast archive!

ADVICE DEP'T.

HEY! DO YOU like advice columns? They don't happen unless you send in some letters! Surely you have something you want to justify to yourself, or to the world at large. Now is the perfect time to share it with everyone else through The Sophist, the columnist who is not here to correct you, but to tell you why you're right. Direct your questions to The Sophist, at indignity@indignity.net, and get the answers you want.

SANDWICH RECIPES DEP'T.

WE PRESENT INSTRUCTIONS in aid of the assembly of sandwiches selected from Benson Woman's Club Cook Book, collected and compiled by Benson Woman's Club, published in 1915 and available at archive.org for the delectation of all.

DENVER CLUB SANDWICHES.

Butter slices of bread. Chip crisp bacon and small amount of onion over bread, add very thin slices of tomato, and sprinkle with salt.

—Mrs. O. S. Brooks.

If you decide to prepare and attempt to enjoy a sandwich inspired by this offering, be sure to send a picture to indignity@indignity.net .

SELF-SERVING SELF-PROMOTION DEP'T.

Indignity is presented on Ghost. Indignity recommends Ghost for your Modern Publishing needs. Indignity gets a slice if you do this successfully!