Slowly trotting home

INDIGNITY VOL. 3, NO. 168

HOUSEKEEPING DEP'T.

GOOD MORNING! It's been a quiet few weeks in the inboxes of Indignity readers, save for the steady and reassuring Thursday presence of the Always Be Columning™ MR. WRONG column. Your Indignity editor spent most of that time in the hospital, for reasons that may or may not eventually manifest themselves in a several-thousand-word essay about health and debility. For now, I'll just say that it was not directly life-threatening but very unpleasant and boring, though I did learn the all-important hospital trick of wearing two gowns at once, one open in back overlaid by one open in front, for comfort and full coverage. And that I would much rather have spent those weeks with you, the readers.

Do bear with us as Indignity and I work on returning to full speed. Your interest and support keep us going, to the extent we keep going. If you're not a paid Indignity subscriber, and you'd like to become one, please use the button right here:

The Weather Reviews will resume when I can reliably get outside; the Indignity Morning Podcast will return when my voice comes back.

Meanwhile, for today, we proudly present a guest post by the incomparable Tommy Craggs. Our deepest thanks to Craggs for helping in our time of need.

ATHLETIC AESTHETICS DEP'T.

The Big-Swinging Phillies Stop Time

By Tommy Craggs

THERE'S A GREAT old line from Bill James, the patron saint of numerical sports analysis, about baseball statistics acquiring the power of language. I thought of it the other day, looking up the numbers for the most compelling player on the most compelling team in the Major League Baseball playoffs right now. During the regular season, Kyle Schwarber of the Philadelphia Phillies hit .197, with 47 home runs, 126 walks, and 215 strikeouts—a remarkable stat line, a report card with A's and F's and nothing in between. Played a bunch of games at DH. Hit only a handful of doubles. Stole no more bases than you or I did this year.

All of it tells a story, doesn't it? If you'd never seen Schwarber in your life, you could get a fair picture of him from his numbers alone. Big dude, surely. Wrists like shipyard rope but soft everywhere else, or at least softening. On the wrong side of his prime, as indicated by the hideous batting average and the gaudy walk totals, which, taken together, carry the poignant suggestion of a ballplayer fighting gamely, with patience and guile, against the senescence of his finer skills. (Or maybe you just think of Rob Deer.) There's pathos in this stat line. Humor, too, of the "aging male wrestles with his encroaching incompetence" variety. These are statistics that not only have acquired the power of language but are apparently going to pilot on CBS next fall.

Last week, in the first inning of Game 1 of the National League Championship Series between Philadelphia and Arizona, Schwarber sent a pitch from Diamondbacks ace Zac Gallen in the direction of Moab, Utah. It was his first home run of the playoffs, a 420-footer, and over the next four games he would go on to hit four more. Going into tonight's Game 7, the Phillies as a whole have hit 23 homers this postseason, a mile and three quarters' worth of them by our math.

If you're only just now floating into the baseball season and you watched the game or caught the highlights, you might've noticed a curious thing in the background as Schwarber made for the dugout: a digital clock beginning its countdown. This season, MLB implemented a pitch clock to curb all the skylarking and obsessive scuffling during the interstices of actual play, thus shortening and, maybe more significantly, normalizing the duration of games. (TV loves predictability, after all.) In a way it was a familiar story—the great American speed-up come at last to the national pastime, with players being made to work faster in the hopes of undoing the game-fattening effects of an era in which players had been incentivized to work bigger.

The clock may have cleaned up some of the pointless stalling, but it came at a price for fans, flattening out the tempo of the game to an efficient hum, without the pulse of rising and falling tension. Schwarber and the Phillies have shown us that there's still room for some dilatory pleasures to be had. Among other rules, players now have only 30 seconds between batters to resume play. In the event of a 420-foot home run, however, the batter can seize control of how long the play itself lasts. The clock has to yield while the batter admires his work, gives a matador's flourish to the fans in the outfield bleachers, does a little sightseeing between first and second, handwrites some letters between second and third, takes up analog photography while rounding third, and finally arrives at home plate by way of the Strait of Gibraltar.

How perfect, then, that the clock and the dour Taylorism it embodies have arrived alongside one of the great rip-it-and-pimp-it offenses in recent memory. These Phillies are anachronisms in the etymological sense of the word: They're against time. It's not just Schwarber. It's Bryce Harper watching the first of his two home runs in Game 3 of the National League Division Series like someone pausing to admire an eclipse. It's Nick Castellanos flipping his bat with sublime disgust, as if he were mucking a 2-7 offsuit, then stalking down the first-base line. It's the very philosophy of the Phillies, which is to win a lot by winning expensively—they have more than $1 billion in present and future payroll committed to six players—and not by scratching out runs but by grabbing them by the fistful, big inning by big inning, the games stretching on into the night, unmindful of the TV networks' preference for neatly shaped programming. They're a team built to make the clock wait.

In the pace-of-play era, the showboats are taking a stand. It's as if they're reclaiming their time from baseball's lords of efficiency. This naturally runs up against the many enduring red-assed shibboleths the sport observes, or claims to observe, against oversavoring one's own work. Slow-walking and bat-tossing, the story goes, are antithetical to the way the game is meant to be played, a claim about tradition belied by some of its most immortal highlights. In the tail end of the American League Championship Series, there was a lot of catty business between the Houston Astros and the Texas Rangers' Adolis García. It seems García had caused offense in Game 5 of the ALCS when he celebrated a three-run home run by strolling unhurriedly with his bat and then spiking the thing. He was plunked for his crimes. In Game 6, he responded by crushing a game-breaking grand slam in the ninth, then somehow finished circling the bases at Minute Maid Park in time to hit two more home runs in Game 7 on Monday—marking the first of those, when he finally started moving his feet, by skipping backward toward first base for a few steps.

García and Schwarber and Harper and Castellanos and all the rest know that there are generosities much larger and more important than the cheap, embittered version of sportsmanship being peddled by the Astros. They are showing us one of them whenever they step out of official time long enough to convey just how good it feels to be so good at baseball.

VISUAL CONSCIOUSNESS DEP’T.

Baked Goods at the Diner in That Glass Case They All Seem to Have That’s Usually Right Across From Where You Pay So There’s Lots of Time to Study the Items and Justify Buying a Few to Take Home or to the Office If You Even Work in an Office Anymore.

More consciousness at Instagram.

SANDWICH RECIPES DEP’T.

WE PRESENT INSTRUCTIONS for the assembly of the final and admittedly anticlimactic sandwich selected from Practical Home Economics: 1245 Scientific Recipes, by Alice M. Donnelly A. B., University of Michigan, and Helen Cramp Ph. B., University of Chicago, published in 1919. This book is in the Public Domain and available at archive.org for the delectation of all.

COMBINATION SANDWICH

2 slices whole wheat bread

2 slices cold boiled ham

2 slices Swiss cheese

Butter

Butter the bread. On one slice lay the slices of cold ham; then lay on the cheese; then the other slice of bread and press down firmly. Cut across diagonally and serve.

If you decide to prepare and attempt to enjoy a sandwich inspired by this offering, kindly send a picture to us at indignity@indignity.net.

MARKETING DEP'T.

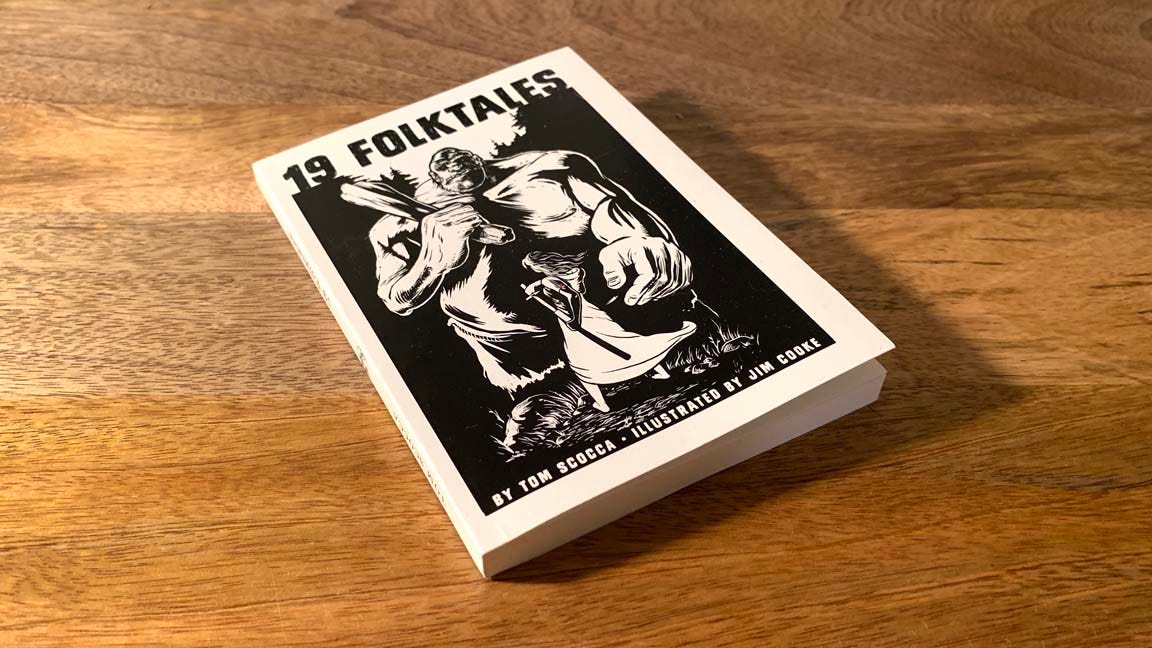

19 FOLKTALES collects a series of timeless tales of canny animals, foolish people, monsters, magic, ambition, adventure, glory, failure, inexorable death, and ripe fruits and vegetables. Written by Tom Scocca and richly illustrated by Jim Cooke, these fables stand at the crossroads of wisdom and absurdity.

HMM WEEKLY MINI-ZINE, Subject: GAME SHOW, Joe MacLeod’s account of his Total Experience of a Journey Into Television, expanded from the original published account found here at Hmm Daily. The special MINI ZINE features other viewpoints related to an appearance on, at, and inside the teevee game show Who Wants to Be A Millionaire. Your $20 plus shipping and tax helps fund The Brick House collective, a Publishing Concern featuring a globally diverse set of publishers doing their own thing, with interesting items and publications available for purchase at SHOPULA.

Thanks for reading INDIGNITY, a general-interest publication for a discerning and self-selected audience. We depend on your support!