Wash those vegetables!

Indignity Vol. 4, No. 130

ANDY ROONEY 2.0 DEP'T.

Keep Your Dirt on Your Organic Farm, I Don't Want to Eat It

I WAS TRYING to make dinner with as little effort as possible, so I was getting some romaine lettuce ready to stir-fry while I let a pot of ribs cook on the stove. I pulled off the first, most beat-up outer leaf from the head of romaine, and down at the bottom, where it met the rest of the head, I saw black dirt. I checked a little deeper into the head and the leaves there had dirt, too. I started tearing the leaves off over a paper towel, to get rid of the heaviest dirt before I put them in a bowl to wash in the sink. Little clods of dirt scattered all over the counter.

This was the organic lettuce. The organic stuff isn't always filthy, but the filthy stuff is pretty much always organic. Somebody somewhere along the line must have gotten the idea that it makes the produce seem more sincere and authentic if they don't wash it, as if I'm buying organic produce because I want to experience some deep connection to the soil—as if I want to get dirt on my hands, possibly even between my teeth or in my belly.

If I wanted to get my hands dirty, I would go live somewhere where I have to grow my own food. Or at least I would sign up for the community garden. When I'm in the galley kitchen of my Manhattan apartment, what I'm looking for from my vegetables is to get them cooked for dinner. Quickly. Having muck all over the groceries—and with one recent bunch of chard, it was really all over the groceries, dirt smeared into the milk cartons that rode in the bag with it—slows everything down.

I read an essay once that I can't figure out how to find again, about how the way everyone talks about food and cleanliness is tangled up between two contradictory ideas about what purity should mean. There is pure as in untainted, the wholesome product of healthy nature, and there is pure as in spotless, scrubbed and disinfected by scientific standards. This is why the idea of irradiated food gives people the willies, for instance—rationally speaking, radiation kills off pathogens, but a dose of gamma rays sounds sinister and unappetizing.

Organic produce is meant to appeal to people who don't want the specter of the unnatural hanging over their food. I personally prefer not to eat pesticides, if I can help it, and I grew up seeing the Chesapeake Bay ravaged by nitrogen runoff from the overuse of synthetic fertilizer. As long as it's not too bug-eaten or wildly overpriced, I'll usually choose organic over conventional produce.

And then I'll find myself up to my forearms in grimy water in the sink, rubbing clinging dirt off a lettuce leaf that would have been pristine if it were conventionally produced, and I'll wonder why I bothered. The thought of bug-killer on the produce may be upsetting, but dirt is dirt and time is money, on top of the money that was money that I already paid for organic vegetables.

Nothing in organic certification says they can't wash the vegetables better! It's not industrial or artificial to get the dirt out of there. The people at the farmers' market don't sell you grubby vegetables face to face, because that would be slipshod and rude, when you're supposed to be buying something someone put some care into.

When I picture organic farming, it begins and ends with somebody lovingly tending to their dirt—enriching and preserving it, rotating their crops on it, plowing supplemental plant matter into the ground to build up ever-deeper, ever-healthier soil. Instead, they're shipping their soil to the produce distributor so I can wash it down my sink and send it on to the North River Wastewater Resource Recovery Facility. It makes me think the farmers must not care very much about their dirt, after all.

SIDE PIECES DEP'T.

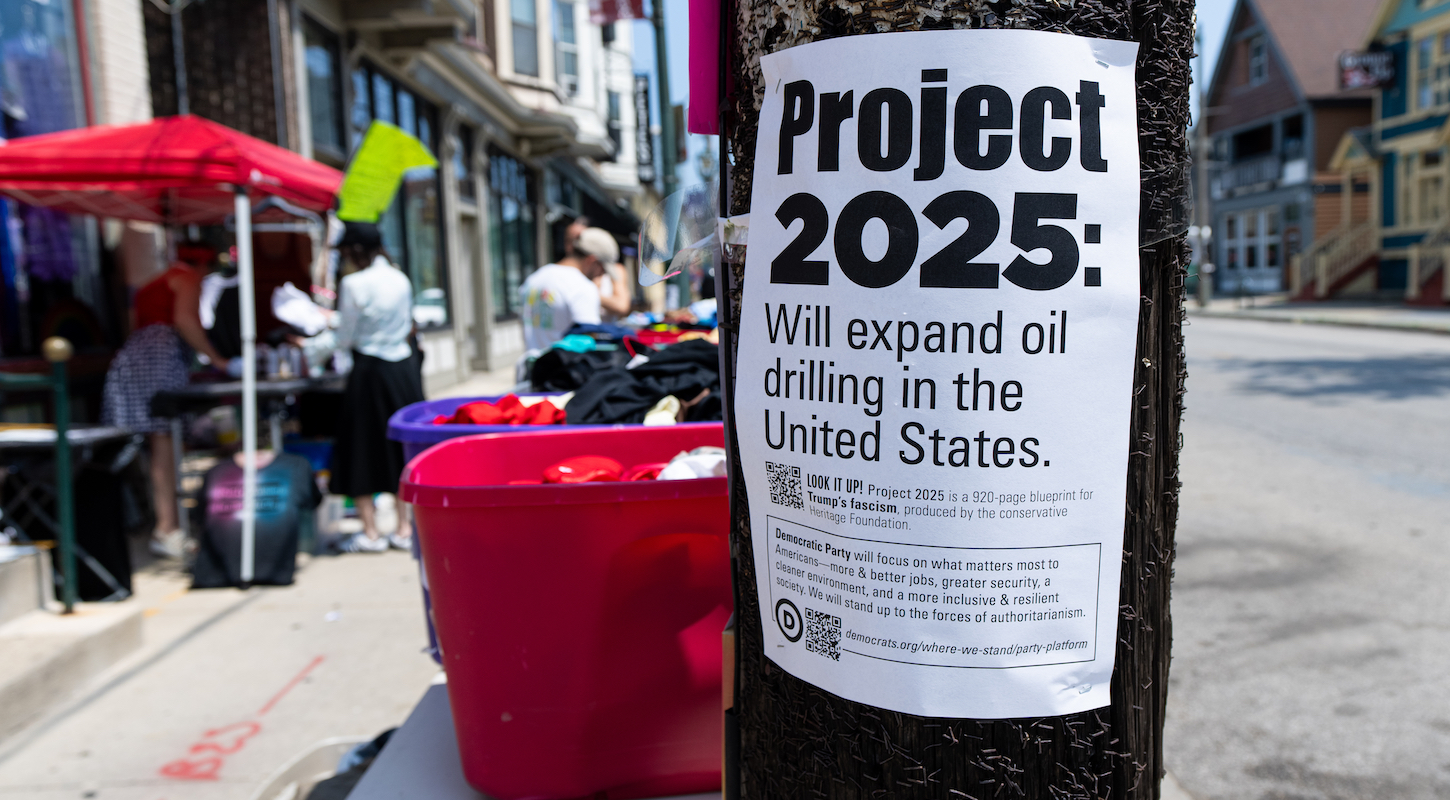

FOR DEFECTOR LAST week, I wrote about the Project 2025 controversy and how, via TikTok, the country might be achieving real civic engagement:

American political campaigning and reporting has been built for generations on the premise that the voting public is hopelessly superficial. People here are expected to vote for the would-be president with the persona that impresses them, the person they think they would want to have a beer with, the one who seems most potently presidential. Sometimes they get mad about the price of gas and want to change things, but the assumption is that the nation holds a big popularity contest, where a genial actor or a charming rogue or an inspiring orator or a pugnacious showman wins a mandate against whatever cold fish or policy nerd the other side comes up with.

Yet here in 2024, in the maelstrom of personality politics, the public is attending to a whole big book of issues. Some of the forces driving that interest are non-wonky—Taraji P. Henson warned the audience about Project 2025 while hosting the BET Awards, making the subject take off on social media; Trump and his campaign clumsily tried to deny their involvement with it, giving the political press license to treat it as a scandal and a cover-up—but also it's a big, long document full of alarming and demented ideas, ideal for people to dig into and find their own points to warn other people about. It is an unsoftened product of the deepest right-wing ghoulosphere. To pick a topic more or less at random, it goes on for six pages about the importance of stopping the Department of Agriculture from feeding too many people, including urging a new Trump administration to "reject efforts to create universal free school meals" and abolish summertime school-meal programs for kids who aren't enrolled in summer school.

EASY LISTENING DEP'T.

CLICK ON THIS box to find today's Indignity Morning Podcast.

SANDWICH RECIPES DEP'T.

WE PRESENT INSTRUCTIONS in aid of the assembly of a sandwich selected from Mrs. Ericsson Hammond's Salad Appetizer Cook Book, by Maria Matilda Ericsson Hammond. Published in 1924, and now in the Public Domain and available at archive.org for the delectation of all.

Tomato Sandwiches with Cheese à la New York

Sandwiches de Tomate au Fromage à la New -York

For Six Persons

Six slices of bread. One cup of grated American cheese. Three even-sized tomatoes. Whites of two eggs, pepper and salt.

How to Make It. Slice the bread and cut it out with a large patty cutter. Spread it with butter and the grated cheese, sprinkle with cayenne pepper and salt. Put it on a baking sheet in the oven for about three minutes. Skin and slice the tomatoes in even slices. Place one on each of the cheese sandwiches. Sprinkle it with cheese. Put them in the oven for the second time for about four minutes. During the time beat the whites of the eggs to a meringue. Put it in a paper bag that holds a fancy tube. Decorate with the meringue a ring around each and on top of the tomato a rose. Put a dice of the tomato dipped in chopped parsley in center. Put in the oven for four minutes until the whites are light golden. Arrange on the platter and garnish with parsley. Serve as a savory for luncheon or dinner.

If you decide to prepare and attempt to enjoy a sandwich inspired by this offering, be sure to send a picture to indignity@indignity.net.

MARKETING DEP'T.

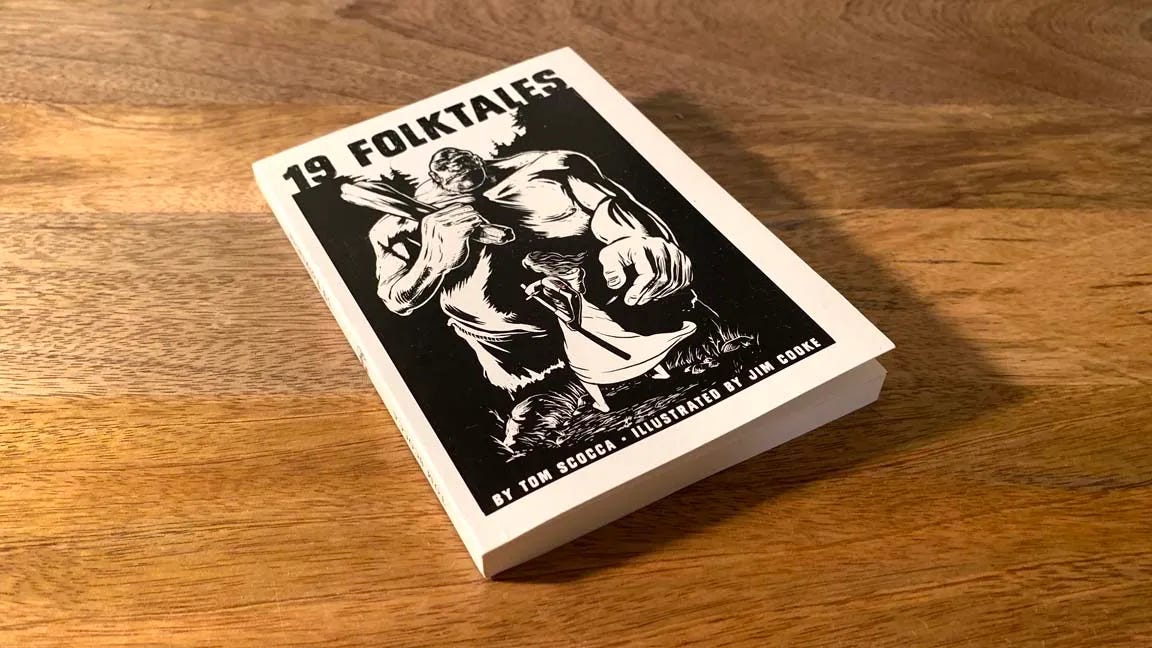

Supplies are really and truly running low of the second printing of 19 FOLK TALES, still available for gift-giving and personal perusal! Sit in the crushing heat with a breezy collection of stories, each of which is concise enough to read before the thunderstorms start.

LESS THAN 5 COPIES LEFT: HMM WEEKLY MINI-ZINE, Subject: GAME SHOW, Joe MacLeod’s account of his Total Experience of a Journey Into Television, expanded from the original published account found here at Hmm Daily. The special MINI ZINE features other viewpoints related to an appearance on, at, and inside the teevee game show Who Wants to Be A Millionaire, and is available for purchase at SHOPULA.