Indignity Vol. 1 No. 3: Maybe Andrew Cuomo is bad?

THE WORST THING WE READ THIS WEEK™

When Was It Time for Andrew Cuomo to Go?

“YOU SHOULD RESIGN, Governor Cuomo," the New York Times editorial board declared in a headline August 4. It was a would-be serious message made comical and baffling by its timing in the news cycle, the newspaper gravely presenting its official verdict on Cuomo nearly 24 hours after even President Joe Biden had already said the same thing—the Times' opinion editors sprinting up to an already overfilled CUOMO MUST GO kiosk, stapler in hand, fumbling through the sheaves of accumulated notices for some space to tack up their contribution.

But the argument was even more ludicrously belated than that. Here is what the Times editorial board thinks about Andrew Cuomo: the governor has "a reputation for vindictiveness." He is "bullying in his use of power," and "his ethics record remains a black mark."

That wasn't how they made their case this week for removing him; it was how they made their case three years ago for reelecting him, as he sought his nomination for a third term in the Democratic primary. Yes, the board conceded, Cuomo was a shady operator and a nasty goon, and yes, he had blocked reform and ruined the subway, but—

"When Mr. Cuomo is focused on governing," the board wrote then, "no New York politician in memory has been as effective."

It wasn't true then. Now, with some 12,000 New York nursing-home residents dead of COVID-19, a death toll driven by the governor's bungling—and with Cuomo's office caught trying to hide one-third of those deaths in deceptive paperwork—the falseness should be indisputable. Yet the Times kept on clinging to the nonsense, even as the editorial board finally gave up on Cuomo's governorship, confronted as they were by Attorney General Letitia James' thorough and merciless investigative report into Cuomo's apparently habitual and prolific sexual harassment:

Mr. Cuomo has always had a self-serving streak and been known for his political bullying. He also has used those traits to be an effective politician and, in many of his achievements as governor, won the public’s trust. What this report lays out, however, are credible accusations that can’t be looked past.

Setting aside the parts about Cuomo's effectiveness and "the public's trust" as the hand-flapping rationalizations they are, the reader of both editorials, from then and from now, is left to puzzle over what "however" is supposed to convey here. What has changed since 2018, exactly? Is it the difference that credible accusations of harassment exist now, and did not exist before? Or is it that now such accusations cannot—in the careful passive construction of the editorial board—"be looked past"?

Sexual harassment, specifically, may be a relatively new addition to Cuomo's public portfolio. But Andrew Cuomo has been widely understood to be a loathsome scumbag since he was a young lad denying all responsibility for the "VOTE FOR CUOMO, NOT THE HOMO" slogans that accompanied his father's 1977 mayoral campaign against Ed Koch. Again, here are the Times editors in 2018:

Mr. Cuomo pledged to clean up Albany in his first campaign for governor. Yet instead of confronting the ethical horrors of the state capital, his administration has added to them. This year his former campaign manager and closest aide, Joseph Percoco, was convicted on corruption charges, and Alain Kaloyeros, a key figure behind the governor’s signature upstate economic plan, was convicted in a bid-rigging scandal.

Note: "his first campaign." And this was his third campaign, and the Times wasn't simply declining to endorse his challenger (the way it handled his second campaign, decrying Cuomo's failure to reform Albany but refusing to get behind the reformist campaign against him); it was concocting a whole fable of a bold but wayward man-child just waiting for a crisis to reveal his true strength and leadership, so that it could tell voters they should actively go out and support him.

What the Times really meant was that the voters were going to vote for Cuomo anyway, and that none of the wrongs he had committed could make a difference. The job of a major newspaper's editorial board is to chase after consensus while pretending to be establishing it—to describe what it believes can happen, in the guise of prescribing what should. Its members are bound by the limits of the moral and political imagination of whichever wealthy person owns the newspaper, and by their own fears of demonstrating their lack of influence, which together they internalize as a sense of responsible, objective-minded pragmatism.

Cuomo, however, has made a long-running farce out of this effort to justify the way things are. There is no uplifting language to describe the trajectory of his career. There is, even now, no moral to the story.

Instead there is the uncomfortable, half-latent understanding that throughout the span of events known as the MeToo movement, the public or journalistic story about what's happening—roughly speaking, that society has agreed to stop tolerating sexual misconduct and other forms of abuse, and to finally start holding perpetrators accountable—has never quite fit the visible sequence of facts. There are causes and effects at work beyond improved societal standards or an awakened sense of justice.

Why are there multiple accusers against Andrew Cuomo now, with the kinds of corroborating witnesses that satisfy the journalistic and political requirement to count as "credible"? Clearly Cuomo has been this kind of creep for a long time, and he has done it in the media capital of America. But evidently no one he'd targeted felt secure enough to come forward.

The cynical but obvious explanation for this is that, until recently, there was no meaningful political force to oppose Cuomo. For his first two terms, he kept the state legislature divided and hapless, by supporting an obstructionist bloc of Democrats who kept a Republican minority in charge of the state senate. When voters broke that bloc's hold, it broke Cuomo's unilateral control on New York politics.

This has been the darker, parallel story of the age of accountability all along. Harvey Weinstein was a monster, yes, but he was a monster for decades, with police and prosecutors holding evidence of his monstrosity, and no one tried to slay the monster until his power and standing in Hollywood had slipped. Jeffrey Epstein could be arrested at last, but the household names on his flight logs have been found guilty of nothing but bad taste in associates. For every open secret that's become a scandal, there are more that keep lurking, never making headlines.

Donald Trump, with his usual gift for turning subtext into text, proudly made a mockery of the whole idea that ethics or morality alone could decide anything. Neither sexual assault nor obvious financial corruption could count against him in the way that these things were supposed to count against a politician. He chose not to care, and no one could make him.

This was the Cuomo approach. As of right now, it still is—the governor remains the governor, even as the Times politely asks him to "do the right thing" and resign. Cuomo continues to believe there's nothing he can't bully his way through. It's the message he's been reading in the newspaper for years.

BRAIN ITCH DEP’T.

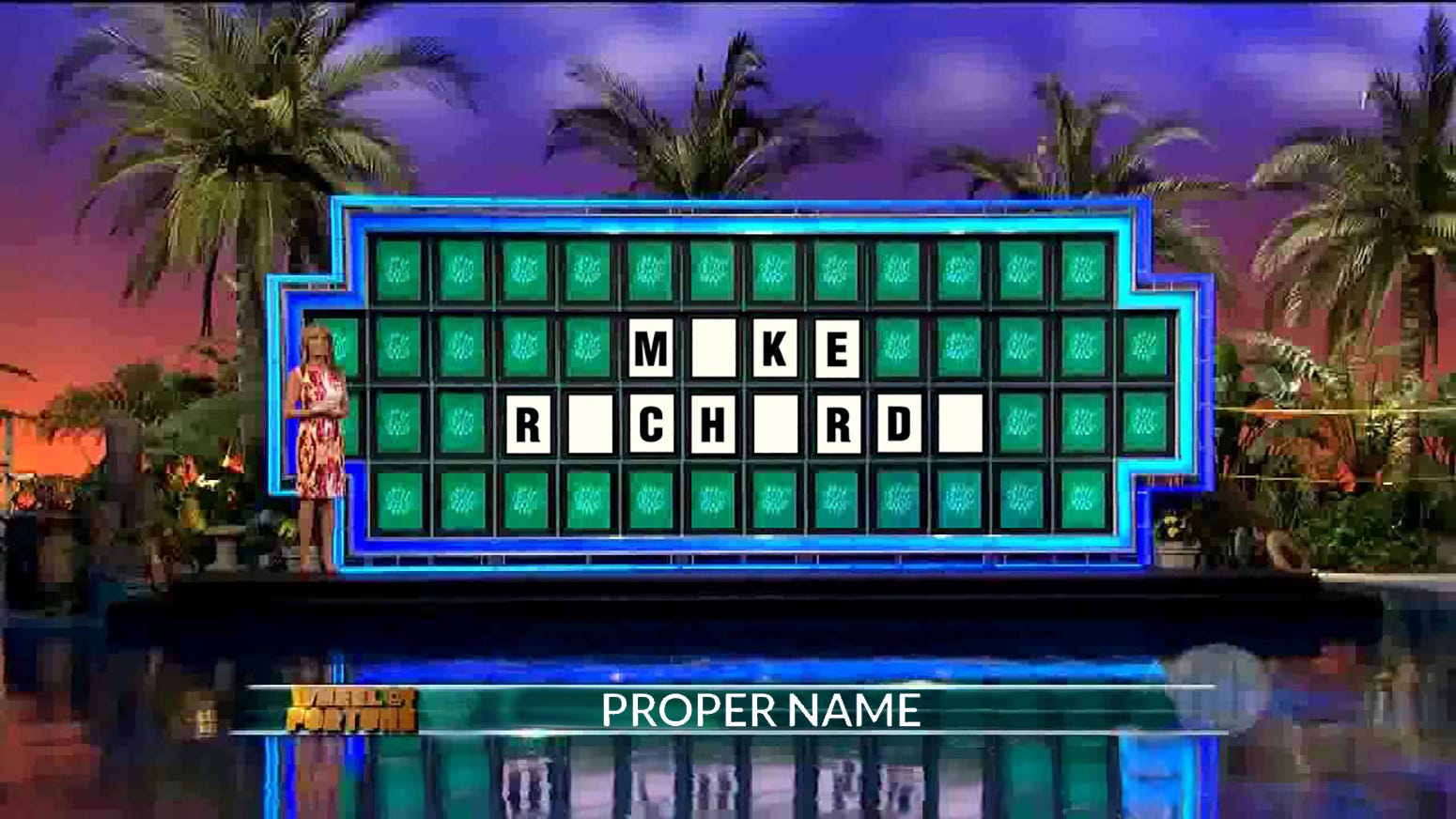

Who Is…the Winner?