Third base, heading for home

INDIGNITY VOL. 3, NO. 162

ATHLETICS DEP'T.

Brooks Robinson, 1937–2023

THERE WAS NO one who compared to Brooks Robinson in the Baltimore where I was born, and there never could be. And the town was rich with sports heroes in 1971, absurdly so. On fall Sundays, the roar of the football crowds washed over our rowhouse from Memorial Stadium, as the fans poured out their feelings for Johnny Unitas, the greatest quarterback the NFL had ever seen, nearing the end of his Colts career. People worshiped Unitas and the Colts; they could dine out at his restaurant, the Golden Arm, or get a burger from his championship teammate Gino Marchetti, at Gino's. The Bullets had three future basketball Hall of Famers—Wes Unseld, Earl Monroe, and Gus Johnson—leading them into the NBA playoffs.

As for the Orioles, who would be the focus of my world—the Orioles were the reigning champions of baseball, in the midst of a spree of three straight 100-win seasons and 18 consecutive winning seasons overall. They still had Frank Robinson, the mightiest player ever to wear an Orioles uniform, and big Boog Powell, the 1970 MVP, and an untouchable starting rotation, and tiny, furious Earl Weaver giving orders from the dugout or rocketing up onto the field to berate the umpires. I absorbed this knowledge before I was out of diapers; there was never a time I didn't know the Orioles.

And the Orioles were Brooks Robinson. They were Mark Belanger, too, and Paul Blair and Elrod Hendricks, and for one wild and confounding season they were even an unwilling Reggie Jackson, but above and beyond that they were Brooks Robinson. The calendar said he was 34, entering the long, bright late afternoon of his career, but Brooks existed in an eternal present. He'd leapt high in the air—unbelievably high, with his unimpressive legs—with a wide-open grin for his teammates, when the Orioles finished off the Dodgers in 1966, and he'd never really come down.

Stone bald under his caps and toupees, and with those legs slowing down even more than before, he was still unassailable. Back in the '50s, he'd taken a long time to stick in the majors, five years shuttling up and down, scuffling at the plate, punctuated by a freak accident in 1959 where he impaled his right biceps on a metal hook while chasing a foul ball into a minor-league dugout. When he made it to Baltimore as a full-time player the next year, though, at age 23, he batted .294, finished third in the MVP voting, and won the Gold Glove at third base. He would keep on doing that, more or less, for another decade and a half—the Gold Gloves especially and relentlessly, 16 in a row. He was the best defender who'd ever played third base.

He didn't look like what he was. He had slumped shoulders and seemingly plodding feet, and no one would have taken him for the most dominant athletic presence in a clash of two of the most powerful teams in the history of the game, but there was the 1970 World Series MVP trophy and the new Dodge Charger that went with it, to say otherwise. “If we knew he wanted a car so badly, we'd have given him one before this thing started,” the Cincinnati Reds' superstar catcher Johnny Bench reportedly said, after Robinson hit .429 in the series and suffocated the Reds' offense with his glove. Or else Pete Rose said it; the credit varies. Even while Robinson was burying the Reds, they were falling over each other to come up with the best one-liners about what he was doing to them. (Manager Sparky Anderson: “If I dropped a paper plate, he'd pick it up on one hop and throw me out at first.”)

He was a civic possession, and he possessed the city right back. For years I had—every child had—a pullover orange No. 5 jersey, the greatest of all ballpark giveaway prizes, polyester-knit with a V neck. My brother additionally had a white Orioles jersey, from a Halloween costume or something, and he would choose between them as we vied to see, when we got to the stadium, who matched what the Orioles were wearing that day. I wore the Brooks jersey till it fell apart, which took years, tough as the synthetics were. Finally the stitching around the bottom wore out and the fabric began to unravel, one fluffy zigzagging orange strand at a time.

Robinson did a hard thing incredibly well, and he made millions of people happy doing it. The public loved him. His teammates, by all accounts, loved him. Coming out of segregated Arkansas into a far from fully integrated sport, he won the trust and affection of his Black colleagues and opponents. "I never heard anything negative about him, ever," the 1970s Braves and Dodgers outfielder turned current Houston Astros manager Dusty Baker said.

You're supposed to be wary of your sports heroes, as you get older and learn more about the waywardness of humankind. But the figure of Brooks Robinson never got a dent in it. People named their kids Brooks, and it turned out fine. The only sourness around his career wasn't his fault at all; it was the fans' resentment of Doug DeCinces, the perfectly good third baseman who had the bad luck to take over from Robinson at the end, and who had his best season after being mercifully traded to the California Angels.

Beyond that, there was no real letdown when Robinson's playing days were over. He moved into the broadcast booth, a good-tempered and upbeat color commentator, too scrupulous to be a real homer. His twanging, gentle voice carried along the summer nights, a friendly constant through whole new rosters' worth of Orioles—some legendary, some terrible, none of them Brooks.

The year after Brooks retired, we moved out to the country, to Aberdeen. Cal Ripken Jr. had just graduated from Aberdeen High School, and would soon enough be the defining player of my youth and young adulthood: his easy, flawless defense at shortstop; his slugging heroics out of a constantly tinkered-with batting stance; his stubborn endurance in the lineup; his elevation to a national icon. But Ripken's human dimensions were encased in some larger, unavoidably impersonal, level of fame. He may have come from Aberdeen, but he lived in a mansion in Baltimore County, at a now-necessary distance.

Brooks was simply around, wreathed in glory but emphatically life-sized. One time he showed up, in the flesh, as guest of honor at one of our Boy Scout dinners. When the program was done, I besieged him with a whole stack of torn-out rectangles of looseleaf paper, to turn into a whole stack of autographs, and he obligingly did this stupid thing, sitting at his banquet table in the auditorium or gym, because a kid had asked him to. I got so many Brooks Robinson autographs out of it that I don't know where a single one might be today; I handed them out to friends, or tucked them into the plastic front of a school binder, or did who knows what. I wasn't even trying to be greedy, though I was certainly not very considerate of his time. It was just that one autograph could never have been proportionate to what he meant. And he meant that much to everyone.

WEATHER REVIEWS

New York City, September 26, 2023

★ The first vehicle around the corner had its wipers going. The one behind it didn't but the windshield was still framed with water around wiper tracks. A woman crossed the street with a child in tow and a pink umbrella balanced on a stroller in front of them. Out in it, everything was cold again, raw again, gray again. A dog had somehow managed to pee enough on the saturated ground to leave a smell in the air. With the humidity still refusing to drop on schedule, there was nothing to do but stretch a clothesline across the bedroom, crank up the air conditioner, and hope the already delayed laundry could get dry enough.

EASY LISTENING DEP’T.

INDIGNITY MORNING PODCAST

Indignity Morning Podcast No. 154: Presidential neutrality in labor disputes.

Tom Scocca • Sep 27, 2023

Listen now (5 mins) |

Read full story →

SANDWICH RECIPES DEP’T.

WE PRESENT INSTRUCTIONS for the assembly of select sandwiches from The Modern Club Book of Recipes, contributed By Club Members And Their Interested Friends, compiled and edited by Mrs. Norman S. Essig, Chairman of Home Economics, Modern Club, published in 1921. This book is in the Public Domain and available at archive.org for the delectation of all.

SANDWICH APPETIZER

1/4 lb. Roquefort cheese

1 cake cream cheese

Little mustard

Little salt

Little vinegar to taste

Little catsup

Little Worcestershire sauce

Little cider

Mix Roquefort with a little vinegar and mustard and salt, then add cream cheese, catsup, Worcestershire sauce, and cider stirring all together. Spread on rounds of toast with a narrow slice of tomato across the sandwich.

—Mrs. Harold DeLancey Downs

HOT CHEESE SANDWICHES

1 roll snappy cheese

1 egg

1 tbsp. Worcestershire sauce

1/4 tsp. salt

1/4 tsp. mustard

Bacon

Rounds of bread

Cream cheese, add egg and seasoning. Spread on bread cut 1/2 inch thick. Place slice of bacon on each round, bake in quick oven till bacon is done.

—Mrs. F. R. Savidge

CRACKER SANDWICH

Mix together 1 small jar of McClaren's cheese and 2 tbsp. of mayonnaise. Put 1 green pepper through a vegetable grinder and add it to the cheese.

—Mrs. Harold B. Beitler

CRACKER SANDWICH

Roquefort cheese with enough butter rubbed in to spread, a few drops of Worcestershire sauce and a little prepared mustard. Sprinkle paprika on top.

—Mrs. Harold B. Beitler

If you decide to prepare and attempt to enjoy a sandwich inspired by this offering, kindly send a picture to us at indignity@indignity.net.

MARKETING DEP'T.

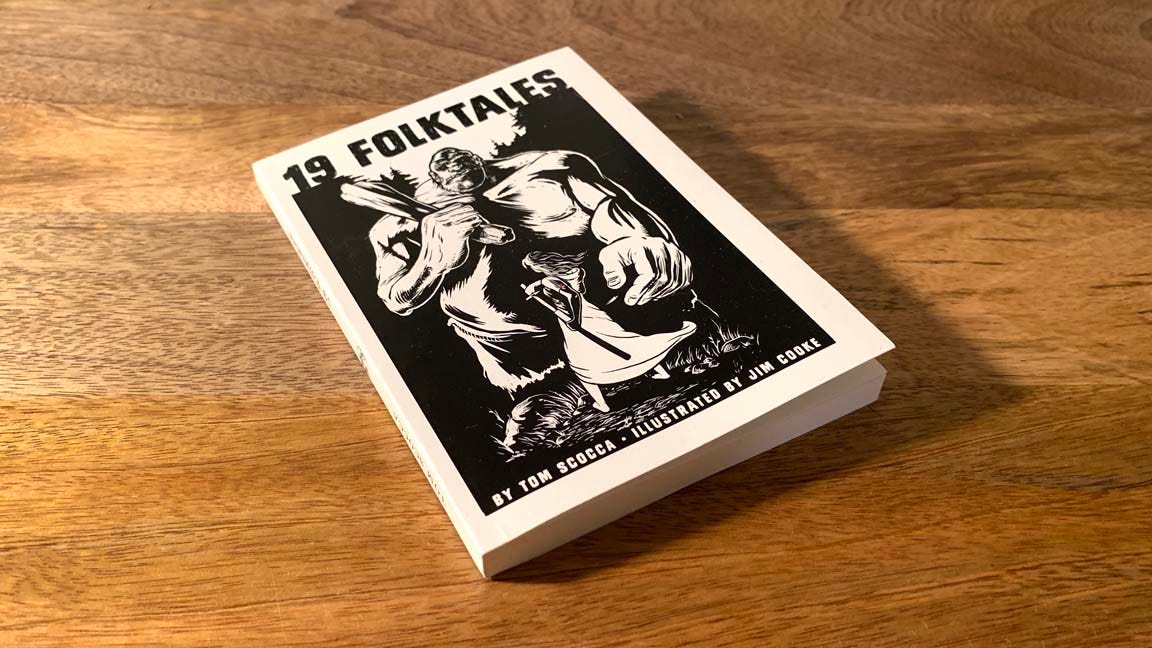

19 FOLKTALES collects a series of timeless tales of canny animals, foolish people, monsters, magic, ambition, adventure, glory, failure, inexorable death, and ripe fruits and vegetables. Written by Tom Scocca and richly illustrated by Jim Cooke, these fables stand at the crossroads of wisdom and absurdity.

HMM WEEKLY MINI-ZINE, Subject: GAME SHOW, Joe MacLeod’s account of his Total Experience of a Journey Into Television, expanded from the original published account found here at Hmm Daily. The special MINI ZINE features other viewpoints related to an appearance on, at, and inside the teevee game show Who Wants to Be A Millionaire. Your $20 plus shipping and tax helps fund The Brick House collective, a Publishing Concern featuring a globally diverse set of publishers doing their own thing, with interesting items and publications available for purchase at SHOPULA.

Thanks for reading INDIGNITY, a general-interest publication for a discerning and self-selected audience. We depend on your support!